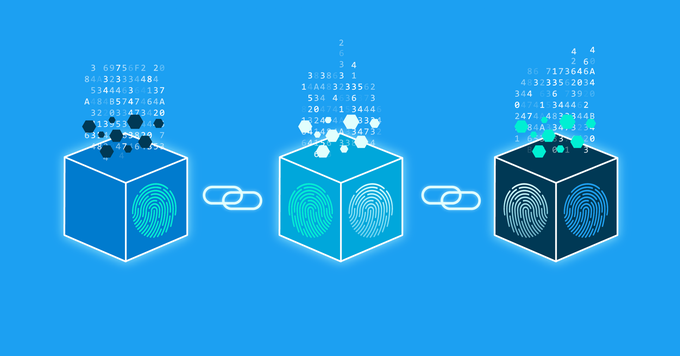

News is proliferating about blockchain and its implications for market research. It might be a way to address, even solve, market research issues like tracing and tracking of the multiple sources of data, identifying all the steps in data retrieval, ensuring against bad data, removing bots as respondents, and helping compliance with new regulations. We might regain our trust in the data underneath the insights, increase transparency, allow the marketer to go direct to consumers by eliminating the research middle ground, and give consumers greater control over data, improving quality of respondents. Some say there is a strong potential to remedy, eliminate, and solve the issues of fragmentation of escalating research techniques. From the GreenBook webinar on August 23, 2018, there is strong emphasis on trust related to blockchain. M. Andreessen is quoted: “Blockchain is the ‘trust protocol’…blockchain enables trusted transactions directly between two or more parties, authenticated by mass collaboration and powered by collective self-interests, rather than by large corporations motivated by profit.” Many inflations and paradigms in research are operating in contemporary marketing—there is an obsession for new research techniques yet increased skepticism that the data is good… desire for more control over data yet slippery commitment issues from team members. Client companies get excited about a highly advertised methodology at the outset and then are unable to follow though in interest because of its complexities and distractions. The mind of the marketer is different from the mind of a researcher; it’s easier to take shortcuts in DIY research when you don’t really resonate to the innate research process and only want results, fast. Researchers have the inherent need to debrief the ambiguities of research findings, reduce the data thoughtfully after we have first expanded it, re-conceptualize the purpose of a study at the midpoint, spot inaccuracies and weird, spooky, or uncanny developments that spell out a major error, winnow out flash-in-the-pan superficialities from highly tested methodologies that have earned our respect, get trained and gain experience in a method, and increase transparencies without causing the consumer to build up defenses that inculcate new emotional defense systems. In a recent seminar on blockchain and market research, certain benefits for each party in the interrelationship are touted and explored. For instance: Suggested benefits for the consumer with blockchain: Consumers can stay involved with the research and data results. This makes the process seem true, relevant, and engaged. But, research gathering is inherently time consuming, consumers are busy, and analysis goes through a shatteringly lengthy, boring stage or two before it gets to interpretation; the best research punctures our egos and tells insights about ourselves we don’t want to know. Good research does not always make our motivations, narratives, and opinions look good to others. Optimum research uncovers shadow needs and wounds as well as light-filled wishes and positive discoveries. So, will consumers have the time, interest, strength of character, and emotional honesty to stay involved with the data and research process? Will they permit their darker side to become known? Suggested benefit for the researcher with blockchain: Blockchain may allow us more trust in the data and the ability to follow the data at every point. It’s said that instead of being nervous about using data that might be corrupt and substandard, we researchers can be bolder. We will know that those who contribute to the data have specific checks, permissions, and have gone through validating identity structures. This will help us relax more and do our work in a more streamlined, trusting fashion. Since the industry is increasingly fragmented and there is proliferation, propagation, and intensification of research techniques, many of which are technology-driven as opposed to tested by social scientists, maybe blockchain will automatically fix this overwhelming aggrandizement. It’s as if a huge picnic table of indiscriminate food brought by unknown providers is laid out on a big lawn and everyone who’s hungry can go get whatever he wants on the basis of taste buds, quality, and perceived value, without having to compromise trust. But, wait a minute, suppose the market research questions are still in the conceptualization stage? Suppose we don’t yet know the competitive framework? Suppose we don’t know what category we’re playing in? Suppose we can’t agree on indubitable questions? Suppose we need a pretest stage or two to figure out what we’re doing? Suppose we are noticing discrepancies between multiple methodologies and their disparate findings? Suppose the research disagrees with the original opinions of top management? It is a maxim that the more thorough, rich, and multifaceted the data, the less direct, obvious, and clear are the resulting data and the greater is the need for careful analysis, skillful reduction. It is frequently the experienced, research team who struggles, smiles, advances, despairs, exalts, goes backward, goes ahead again, and generally pulls out their own hair as they massage the data, allow for ambiguities, reversals, and paradoxes, and then come up with breakthrough results. A quant questionnaire with thousands of undifferentiated respondents that has only three yes-no-maybe questions may be easier to analyze than a client-involved, researcher-led deep-dive qualitative, multiphased, mixed methods, longitudinal methodology about emotional motivations and behaviors of segmentation with a smaller number of algorithmic consumers over a three month period with multiple researchers in several fields, and key variations like ages, segments, and usage categories. But which findings will be more valuable to the marketers? It depends of course, but most likely the longitudinal process. Blockchain is an open decentralized data of transactions involving value. But value in a single consumer’s mind can change from moment to moment depending upon context, mood, income, other actors, wants, and perceived needs. It is this shifting of value that qualitative researchers are trained to notice, become aware of, analyze, and intuit as motivational factors. Suggested benefit for the marketer with blockchain: Theoretically with blockchain, companies, brands, and marketers may be able to reach their consumers directly. The middleman researcher can be fired; done; that was easy. But without the researcher who is trained and innately positioned to have deep unconditional regard and empathy for the human sides of consumers, the same knowledge, depth, objectivity, subjectivity, transcendence of data, and intense level of ethics may not be guaranteed. If the marketer can go straight to the consumer and the consumer can answer the marketer’s questions directly, will the consumer only state what he or she feels it’s appropriate to answer? Will they get bored and stop answering if the inquiry is long or irrelevant? Will they balk and give false data because being asked questions by those who serve to benefit by those answers becomes obvious quickly? Very few like to be grilled by someone or something who is obviously not objective, might abuse trust, and are transparently…opportunistic. Even for trained researchers, it can be hard to ask totally open-ended questions if one has a vested interest in the answer. The consumer can rapidly discern when the questioner (the marketer within blockchain) is asking leading questions without the objective middleman (the researcher eliminated by blockchain). Of course, as a qualitative researcher who is a trained cultural anthropologist and depth psychologist who leads large-scale market research efforts and knows what is entailed under the surface, I and others like me don’t want to be eliminated by blockchain. We don’t even like to be called middlemen. So, I guess this post can be considered suspect or a crusade for the cause of maintaining researchers within the consumer-client research paradigm. We may be in a totally new research ecosystem, but this ecosystem is still not a fait accompli. No one’s fate is being sealed, yet, by blockchain. Blockchain still needs to establish identity structures and do validating research about the authentic nature of data trust so that we can better understand the benefits. When we’re talking about the need for good data, let’s see when there’s significance to having a trained observer research team spearheaded by the qualitative researcher or anthropologist with the ability to dispassionately look at what consumers actually do, don’t do, feel, don’t feel, say, and don’t say. And, let’s figure out together where are the points of definition, devaluation, aspiration, reality, confusion, polarization, ambiguity, and potential transformation. In some ways, the advent of blockchain makes qualitative research seem more radically necessary than ever before. What are the true advantages of no intermediaries, let’s learn who the actors are, see if trust in your specific data is increased or decreased, and begin to differentiate by the specific marketing issue and nature of the explicit inquiry whether blockchain can transform a particular inquiry for the marketer, the brand, the product, or the consumer need…for the better.